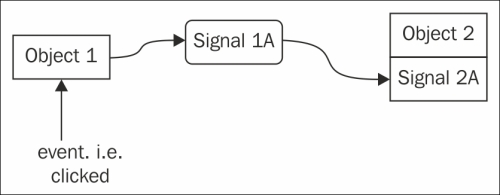

The signals and slots mechanism is a central feature of Qt. In GUI programming, when we change one widget, we often want another widget to be notified. More generally, we want objects of any kind to be able to communicate with one another. Signals are emitted by objects when they change their state in a way that may be interesting to other objects. New-style PyQt Signals and Slots I was to lazy to take a look at the new-style signal and slot support which was introduced in PyQt 4.5 until yesterday. I did know that there were something called new-style signals and slots but that was the end of the story.

Build complex application behaviours using signals and slots, and override widget event handling with custom events.

As already described, every interaction the user has with a Qt application causes an Event. There are multiple types of event, each representing a difference type of interaction — e.g. mouse or keyboard events.

Events that occur are passed to the event-specific handler on the widget where the interaction occurred. For example, clicking on a widget will cause a QMouseEvent to be sent to the .mousePressEvent event handler on the widget. This handler can interrogate the event to find out information, such as what triggered the event and where specifically it occurred.

You can intercept events by subclassing and overriding the handler function on the class, as you would for any other function. You can choose to filter, modify, or ignore events, passing them through to the normal handler for the event by calling the parent class function with super().

However, imagine you want to catch an event on 20 different buttons. Subclassing like this now becomes an incredibly tedious way of catching, interpreting and handling these events.

Thankfully Qt offers a neater approach to receiving notification of things happening in your application: Signals.

Signals

Instead of intercepting raw events, signals allow you to 'listen' for notifications of specific occurrences within your application. While these can be similar to events — a click on a button — they can also be more nuanced — updated text in a box. Data can also be sent alongside a signal - so as well as being notified of the updated text you can also receive it.

The receivers of signals are called Slots in Qt terminology. A number of standard slots are provided on Qt classes to allow you to wire together different parts of your application. However, you can also use any Python function as a slot, and therefore receive the message yourself.

Load up a fresh copy of `MyApp_window.py` and save it under a new name for this section. The code is copied below if you don't have it yet.

Basic signals

First, let's look at the signals available for our QMainWindow. You can find this information in the Qt documentation. Scroll down to the Signals section to see the signals implemented for this class.

Qt 5 Documentation — QMainWindow Signals

As you can see, alongside the two QMainWindow signals, there are 4 signals inherited from QWidget and 2 signals inherited from Object. If you click through to the QWidget signal documentation you can see a .windowTitleChanged signal implemented here. Next we'll demonstrate that signal within our application.

Qt 5 Documentation — Widget Signals

The code below gives a few examples of using the windowTitleChanged signal.

Try commenting out the different signals and seeing the effect on what the slot prints.

We start by creating a function that will behave as a ‘slot’ for our signals.

Then we use .connect on the .windowTitleChanged signal. We pass the function that we want to be called with the signal data. In this case the signal sends a string, containing the new window title.

If we run that, we see that we receive the notification that the window title has changed.

Events

Next, let’s take a quick look at events. Thanks to signals, for most purposes you can happily avoid using events in Qt, but it’s important to understand how they work for when they are necessary.

As an example, we're going to intercept the .contextMenuEvent on QMainWindow. This event is fired whenever a context menu is about to be shown, and is passed a single value event of type QContextMenuEvent.

To intercept the event, we simply override the object method with our new method of the same name. So in this case we can create a method on our MainWindow subclass with the name contextMenuEvent and it will receive all events of this type.

If you add the above method to your MainWindow class and run your program you will discover that right-clicking in your window now displays the message in the print statement.

Sometimes you may wish to intercept an event, yet still trigger the default (parent) event handler. You can do this by calling the event handler on the parent class using super as normal for Python class methods.

This allows you to propagate events up the object hierarchy, handling only those parts of an event handler that you wish.

However, in Qt there is another type of event hierarchy, constructed around the UI relationships. Widgets that are added to a layout, within another widget, may opt to pass their events to their UI parent. In complex widgets with multiple sub-elements this can allow for delegation of event handling to the containing widget for certain events.

However, if you have dealt with an event and do not want it to propagate in this way you can flag this by calling .accept() on the event.

Alternatively, if you do want it to propagate calling .ignore() will achieve this.

In this section we've covered signals, slots and events. We've demonstratedsome simple signals, including how to pass less and more data using lambdas.We've created custom signals, and shown how to intercept events, pass onevent handling and use .accept() and .ignore() to hide/show eventsto the UI-parent widget. In the next section we will go on to takea look at two common features of the GUI — toolbars and menus.

The main interface to PythonQt is the PythonQt singleton. PythonQt needs to be initialized via PythonQt::init() once. Afterwards you communicate with the singleton via PythonQt::self(). PythonQt offers a complete Qt binding, which needs to be enabled via PythonQt_QtAll::init().

The following table shows the mapping between Python and Qt objects:

| Qt/C++ | Python |

|---|---|

| bool | bool |

| double | float |

| float | float |

| char/uchar,int/uint,short,ushort,QChar | integer |

| long | integer |

| ulong,longlong,ulonglong | long |

| QString | unicode string |

| QByteArray | QByteArray wrapper (1) |

| char* | str |

| QStringList | tuple of unicode strings |

| QVariantList | tuple of objects |

| QVariantMap | dict of objects |

| QVariant | depends on type (2) |

| QSize, QRect and all other standard Qt QVariants | variant wrapper that supports complete API of the respective Qt classes |

| OwnRegisteredMetaType | C++ wrapper, optionally with additional information/wrapping provided by registerCPPClass() |

| QList<AnyObject*> | converts to a list of CPP wrappers |

| QVector<AnyObject*> | converts to a list of CPP wrappers |

| EnumType | Enum wrapper derived from python integer |

| QObject (and derived classes) | QObject wrapper |

| C++ object | CPP wrapper, either wrapped via PythonQtCppWrapperFactory or just decorated with decorators |

| PyObject | PyObject (3) |

- The Python 'bytes' type will automatically be converted to QByteArray where required. For converting a QByteArray to 'bytes' use the .data() method.

- QVariants are mapped recursively as given above, e.g. a dictionary can contain lists of dictionaries of doubles.

- PyObject is passed as direct pointer, which allows to pass/return any Python object directly to/from a Qt slot that uses PyObject* as its argument/return value.

All Qt QVariant types are implemented, PythonQt supports the complete Qt API for these objects.

All classes derived from QObject are automatically wrapped with a python wrapper class when they become visible to the Python interpreter. This can happen via

- the PythonQt::addObject() method

- when a Qt slot returns a QObject derived object to python

- when a Qt signal contains a QObject and is connected to a python function

It is important that you call PythonQt::registerClass() for any QObject derived class that may become visible to Python, except when you add it via PythonQt::addObject(). This will register the complete parent hierachy of the registered class, so that when you register e.g. a QPushButton, QWidget will be registered as well (and all intermediate parents).

From Python, you can talk to the returned QObjects in a natural way by calling their slots and receiving the return values. You can also read/write all properties of the objects as if they where normal python properties.

In addition to this, the wrapped objects support

- className() - returns a string that reprents the classname of the QObject

- help() - shows all properties, slots, enums, decorator slots and constructors of the object, in a printable form

- delete() - deletes the object (use with care, especially if you passed the ownership to C++)

- connect(signal, function) - connect the signal of the given object to a python function

- connect(signal, qobject, slot) - connect the signal of the given object to a slot of another QObject

- disconnect(signal, function) - disconnect the signal of the given object from a python function

- disconnect(signal, qobject, slot) - disconnect the signal of the given object from a slot of another QObject

- children() - returns the children of the object

- setParent(QObject) - set the parent

- QObject* parent() - get the parent

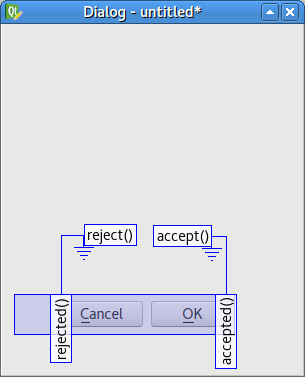

The below example shows how to connect signals in Python:

You can create dedicated wrapper QObjects for any C++ class. This is done by deriving from PythonQtCppWrapperFactory and adding your factory via addWrapperFactory(). Whenever PythonQt encounters a CPP pointer (e.g. on a slot or signal) and it does not known it as a QObject derived class, it will create a generic CPP wrapper. So even unknown C++ objects can be passed through Python. If the wrapper factory supports the CPP class, a QObject wrapper will be created for each instance that enters Python. An alternative to a complete wrapper via the wrapper factory are decorators, see Decorator slots

Signal Slot Python Qt 3.7

For each known C++ class, PythonQt provides a Python class. These classes are visible inside of the 'PythonQt' python module or in subpackages if a package is given when the class is registered.

A Meta class supports:

- access to all declared enum values

- constructors

- static methods

- unbound non-static methods

- help() and className()

From within Python, you can import the module 'PythonQt' to access these classes and the Qt namespace.

PythonQt introduces a new generic approach to extend any wrapped QObject or CPP object with

- constructors

- destructors (for CPP objects)

- additional slots

- static slots (callable on both the Meta object and the instances)

The idea behind decorators is that we wanted to make it as easy as possible to extend wrapped objects. Since we already have an implementation for invoking any Qt Slot from Python, it looked promising to use this approach for the extension of wrapped objects as well. This avoids that the PythonQt user needs to care about how Python arguments are mapped from/to Qt when he wants to create static methods, constructors and additional member functions.

The basic idea about decorators is to create a QObject derived class that implements slots which take one of the above roles (e.g. constructor, destructor etc.) via a naming convention. These slots are then assigned to other classes via the naming convention.

- SomeClassName* new_SomeClassName(...) - defines a constructor for 'SomeClassName' that returns a new object of type SomeClassName (where SomeClassName can be any CPP class, not just QObject classes)

- void delete_SomeClassName(SomeClassName* o) - defines a destructor, which should delete the passed in object o

- anything static_SomeClassName_someMethodName(...) - defines a static method that is callable on instances and the meta class

- anything someMethodName(SomeClassName* o, ...) - defines a slot that will be available on SomeClassName instances (and derived instances). When such a slot is called the first argument is the pointer to the instance and the rest of the arguments can be used to make a call on the instance.

The below example shows all kinds of decorators in action:

Signal Slot Python Qt Download

After you have registered an instance of the above ExampleDecorator, you can do the following from Python (all these calls are mapped to the above decorator slots):

Signal Slot Python Qt Python

In PythonQt, each wrapped C++ object is either owned by Python or C++. When an object is created via a Python constructor, it is owned by Python by default. When an object is returned from a C++ API (e.g. a slot), it is owned by C++ by default. Since the Qt API contains various APIs that pass the ownership from/to other C++ objects, PythonQt needs to keep track of such API calls. This is archieved by annotating arguments and return values in wrapper slots with magic templates:

These annotation templates work for since C++ pointer types. In addition to that, they work for QList<AnyObject*>, to pass the ownership for each object in the list.

Examples: